Joy Unleashed Read online

Page 2

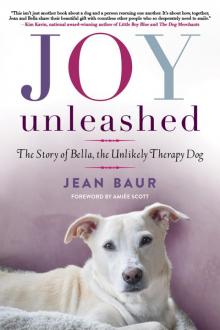

Cuteness won out. Her face got us—and her story. She had been pulled off of Dead Dog Beach at about two months old and she needed a home. Why not us? In hindsight, I could give you a pretty good list of reasons not to adopt her, but we did it anyway. We bought a crate and put her in it in the back of the car, but she was so scared and howling so loudly that we pulled over and let her sit in the back seat. The whining continued and I told Bob to pull over again, thinking maybe she had to do her business. I walked her in the grass at the side of the road but she wouldn’t do anything. About five miles later, she pooped all over the back of the car. Again we pulled over and got the mess cleaned up. Finally, we arrived home and we took her out to our fenced-in backyard and stood with her in the sun. She was so scared that she didn’t take more than a step or two away from us. Bob held her in his arms, and I took their picture.

Our adventure had begun.

Chapter 2

THIS IS A CRAZY PLACE: HOSPITAL ORIENTATION

December 2011–January 2012

St. Mary Medical Center, Langhorne, Pennsylvania

Cathy and her dog, Brandon, as well as another neighbor, Kim, and her dog, Lela, had been taking agility classes with us, but it was Cathy’s idea to switch to therapy dog work. The moment she mentioned it, I knew this was exactly what I wanted to do with Bella. I was done with weave poles, tunnels, and agility trials. After two good years of training, I still didn’t feel that either Bella or I fit. We were never a part of the purebred dog owners group, and I was no longer willing to spend every Saturday driving to agility trials where there was endless waiting combined with heart-stopping panic and worrying about all the rules. All this anxiety crested when they called, “Bella, All American!”—a very nice way of saying “mixed breed”—and we charged through the obstacles, me praying that Bella would remember her hours of training and not shoot through a tunnel the wrong way or jump off the teeter. I enjoyed seeing the dogs who did this beautifully, but given my competitive nature, I felt defensive about Bella’s wild streak and was not willing to put in the work that might make her more like them. In the few trials we did do, I ended up mad at the judges, as well as disappointed in Bella and myself. The experience left a bad taste in my mouth, and I couldn’t deal with more loss now that I had been notified that the job I’d had for the past sixteen years would be ending in a few weeks.

Cathy had done all the research and had connected with David, who had started a therapy dog program at our local hospital in Pennsylvania a few years earlier. He worked as a jeweler and had a busy schedule, so it took a few weeks to pin him down. About ten years earlier, he’d had a heart attack, and during his long convalescence, his wife brought his two dogs into the hospital. Although he still had a long road ahead of him, he noticed the dogs made him feel better, and that when he walked them around the ward, the other patients wanted to see them. This was around 2000 or 2002, and back then, dogs and hospitals were not generally seen as an acceptable pairing. Administrators worried about germs and about dogs upsetting patients, liability issues, and so on.

But David had experienced firsthand what it was like to have dogs as part of his healing regimen, and he fought hard to have them admitted to this hospital. At first, he and the other volunteers were only allowed in waiting rooms, and then in just a few other places. But by the time Cathy and I started volunteering, we could go pretty much everywhere except maternity, surgery, or into rooms with patients who had communicable diseases or compromised immune systems.

At 7 p.m. one cold December night, Cathy and I drove to the hospital together, gave the dogs a few minutes to do their business on the frozen grass, and then had the surreal experience of walking into the hospital with two dogs. People stopped dead in their tracks. Some did a double take. Others backed away. Cathy and I smiled and tried to look as if we knew what we were doing. We went to the main desk and told the woman that we were meeting David for our therapy dog orientation. She told us to wait over by the chairs. Bella looked around, clearly on high alert, while Brandon—always Mr. Cool—sat quietly by Cathy’s feet.

A few minutes later, David came into the hospital with his two Portuguese water dogs, and I saw the hair stand up along Bella’s back. I kept her behind Brandon, who also had issues with other dogs, but who at this moment seemed relaxed and happy. We were now a pack of four dogs and three people, and I was excited for the first time in months. Even though we hadn’t done anything, I felt a sense of purpose and belonging.

“Let’s go up to the fourth floor,” said David.

We followed him and filled up much of the elevator. I noticed a few older people who were waiting for the elevator decided to wait for the next one. Bella had never been in an elevator but didn’t seem to mind. I had a firm hold on her leash, as I didn’t want her near David’s dogs. They ignored her and acted as if nothing special was going on.

We quickly learned the protocol: pick a floor, go to the nurse’s station, and ask if any patients would like a visit from a dog. Check the signs on each door to make sure we were allowed in. Ask the patient if he or she would like a visit from a dog. If yes, spray the bottom of the dogs’ feet with a mild disinfectant, squirt some on our own hands from one of the foam dispensers outside the patient’s room, and walk over to the bed, being very careful not to trip over any tubes or other medical equipment. Then introduce the dogs:

“This is Bella and Brandon and they’re here to visit.”

See if the patient wants to pat them, or if they’d prefer that the dogs put their front paws on the bed, or in special occasions, jump up on the bed. (I couldn’t believe the hospital allowed this.)

Cathy and I followed David and glanced at each other as we left each patient’s room. Neither of us were sure we could do this. And to top it off, I was convinced that I would get lost in this huge, rambling hospital and would never find my way back to the main lobby. I tried to pay attention, but most of all, I was overcome by seeing, for the first time, the powerful effect the dogs had. Tiredness became excitement, isolation was replaced with companionship, and loneliness was forgotten. Brandon sauntered into these rooms, looked casually around, and if we stayed long enough, he sat down. Why not take a little rest? Bella, on the other hand, was nervous. There were strange noises and stranger smells, and she was reluctant to get near the beds and wheelchairs. She stuck very close to my legs and gave Brandon a lick on the mouth when we were out in the hallway.

“Get the basic idea?” asked David after we had seen a half-dozen patients.

Cathy and I nodded.

“Some patients won’t want to see you, and you can always ask at the nurse’s station if there is anyone you should make sure to visit.”

He led us to the elevator and we returned to the ground floor. He showed us where the volunteer office was and where to sign in and out. They had bottles of spray for the dogs and he told us to take one. He reminded us of the cardinal rule: we were never to ask about a patient’s condition. We weren’t there to offer advice, and we never talked about the patients unless there was an issue that needed to be reported to a nurse or the volunteer supervisor.

“You’ll also be getting special leashes. St. Mary’s doesn’t use the volunteer jackets for pet therapy work, but you’ll have a nice blue leash with St. Mary Medical Center written on it. Make sure to use that and to wear your name tags. You can wear your dogs’ name tags, too, or clip them to their collars.”

There was so much to remember. We thanked David, put on our jackets and gloves, and headed out into the cold night.

“Got that?” I asked Cathy as both dogs squatted in the brittle grass. We burst out laughing.

“Good thing we’re doing this together,” said Cathy, and I agreed. I wasn’t a shy person, but this felt overwhelming and we were both afraid of doing something wrong.

Brandon and Bella were happy to be outside. They sniffed their way to the car and we drove home. Cathy and I told the volunteer office that we would come every Monday at 1 p.m., starting

in January. I was grateful for this structure; I didn’t know what I was going to do without work. It was going to be very strange to have all this free time. Well-meaning friends told me that everything was happening for a reason, but I was never a big fan of that concept. I couldn’t find a reason for my job loss that made sense to me, and although I could guess why my name was on the list, I was still in that hurt, “why me” phase and wasn’t sure how to break out of it. To top it all off, a career coach losing her job was supremely ironic—like a doctor getting sick.

I loved my work, but I was beginning to realize I had outgrown the industry I’d been in for sixteen years. I had grown up in the industry when personal attention and deep relationships were deeply valued, but at age sixty-five, it was clear that I had never adjusted to the increasing pressure to see more clients and give them less time. So I wasn’t only mourning my job loss, but all that had been lost over the past few years.

“This was the best,” said Cathy as she dropped me off. I agreed. It really was. I was deeply grateful to have something new and hopeful in my life. I was also grateful for her.

I gave her a big hug.

Chapter 3

THE CAT IS NOT A SNACK

June 2007

Yardley, Pennsylvania

The crate we’d bought saved our life. Bella had never been in a home and was wild. She flew through the air at warp speed, crashed into furniture, jumped over chairs, and only focused on two things: digging and chewing. She ate one of my leather sandals. She devoured a decorative pillow and chewed through the mat and towels in her crate. Our backyard looked like a moonscape from Bella’s craters. She was so out of control that we had to keep her on the leash in the house, and walking her was a lesson in frustration. She pulled, veered, stopped abruptly, and was afraid of plastic bags and the ceramic frog in our front garden that Bob’s mother had made for us.

I worked from home two days a week and was in the office for the other three, but poor Bob, who was off for the summer, got to be with Bella every day. He was on the brink of a meltdown. And while we both knew it was unfair, we couldn’t help but compare her to Angus—our sixteen-year-old mellow dog who, even in his youth, couldn’t touch Bella’s energy. It was like having another species in our home—something completely foreign and destructive.

Henry, our three-year-old cat, also a rescue, liked to think he was a dog and was unafraid of this whirling dervish. This wasn’t really smart on his part—we had no idea what Bella would do around him. On about our fifth day with Bella, I was upstairs getting ready for work and I heard Bella tearing through the house after Henry. Her nails slid on the hardwood floors, and I heard an occasional crash as she collided with anything that got in her way.

“Bob!” I shouted. “What’s going on?”

“Thought I’d see how they work it out themselves.”

“Are you kidding?”

I ran downstairs half-dressed to find Bella barking at the couch. Henry had wisely gotten himself under it where she couldn’t reach him.

“Crate time,” I told her, putting her in the crate with a treat. “Henry is not a snack. You can play but you can’t hurt him.”

She looked at me with her deep brown eyes, as if saying “Really?”

“Be a good girl and have a little quiet time.”

She flopped down on her side and chewed on the thick mat that lined the bottom of the crate. I ran back upstairs, finished getting ready for work, and gave Bob a kiss.

“Hang in there,” I told him. “It’s going to take time.”

I could see from his face that he was having serious doubts. We both were.

“I’ll do some research at lunch time,” I told him, “and find an obedience class. Other people make it through this.”

“Maybe they use drugs,” muttered Bob.

“For the dog or for themselves?” I asked.

“Let’s go for both.”

As I drove to work, I realized we were in for a long, slow process—one with uncertain outcomes. But I also knew we were going to do it—we were going to make it work. There was nothing sweeter than Bella curled up on top of Bob, her pink belly facing the ceiling, her long thin legs stretched straight up in the air.

Next challenge: housebreaking. Kim from St. Hubert’s had said to take her outside of the crate immediately and to use an authoritative command such as “Do your business.” We tried it and sometimes it worked. But to get to the back door, we had to go through the family room, which had wall-to-wall carpeting, and Bella often peed a few paces from the door.

“No!” we shouted, and dragged her outside, using the “Do your business” command. I spent a lot of time on my hands and knees with a miracle spray that was supposed to break down the enzymes of dog pee. One good thing—she hadn’t pooped in the house.

Our close neighbors, Jim and Jodi, also had a new puppy, Cooper, a yellow lab. Jodi and I decided to hire a dog trainer to come once a week to teach our wild puppies how to behave. The problem was, Bella was so excited to be with Cooper in every session that she didn’t pay any attention to the basic commands like sit, stay, or heel. She thought it was play time and hurled herself underneath Cooper, biting at his chest and face. Cooper was happy to go along with this plan, until finally Jodi and I got them separated.

We had homework: Bella—sit. Bella—stay. Bella—come. We used treats as lures and sometimes they worked. Bella—heel. We practiced in the house and in the backyard. When she pulled when we were out walking, I stopped and didn’t continue until she walked nicely beside me with a loose leash. It took forever. I wished she could be off-leash the way Angus always was; it was so frustrating being tethered to this high-voltage creature. I had expected training to be easy. I had expected quick results. I wanted her to get an A from the trainer. It didn’t happen.

I made up a poem to help myself get through it. It started with: “There is nothing merrier than a crazy little terrier.” Actually, that’s as far as I got except that I changed the word crazy to wild, or stubborn, or head-strong. It was my mantra. I repeated it endlessly—in my head, out loud, sometimes turning it into a song. This silly poem helped me realize that Bella and I were a lot alike; and although I wouldn’t admit it, I admired her fierce independence and determination.

On one particular walk, Bob and I were struggling up a hill in our neighborhood with Bella darting this way and that when we saw another couple and their dog walking behind us. It was Cathy, John, and Brandon, and luckily for us, the two dogs liked each other right away. Cathy saw the discouragement in our faces and told us not to worry—that it took about two years for a dog to settle down and really get it.

“Are you kidding?” I asked. “Two years?”

Cathy looked at John, who nodded. “Yes—that’s about right. Of course it gets easier along the way, too.”

Bob and I groaned.

“You’ll make it,” said Cathy, the eternal optimist. “Just look at how cute she is!”

And she was right—Bella was really cute with pink spots on her nose and a face that radiated curiosity and sweetness. As we walked along together, we shared our list of grievances, and John suggested getting an Easy Walk harness so that Bella couldn’t drag us down the street. We’d never heard of such a thing, but were ready to try anything that made walking easier. Bella often got three good walks a day—our desperate attempt to tire her out.

We bought the harness, and witnessed a miracle. The harness clasp was on the chest, not the back, so that if the dog pulled, he or she was forced to turn into you and therefore couldn’t keep moving. It may have seemed like a small thing, but it saved us from constant frustration, from that terrier drive and leader-of-the-pack mentality. It wasn’t perfect—Bella still didn’t understand the concept of walking along beside us—but it was a huge help. Maybe we would make it after all.

Chapter 4

THE INFUSION ROOM

February 2012

St. Mary Medical Center, Langhorne, Pennsylvania

&nb

sp; My best friend from college, Nancy, had been diagnosed with breast cancer. It seemed like a bad dream. Unreal. She didn’t tell me about it for weeks. And hanging over her was the shadow of her mother’s early death from cancer at age fifty-two. Nancy and I lived several hours from each other, so I couldn’t take Bella to see her, but in her honor and to get a glimpse of what she was going through, I decided that Bella and I would visit the Cancer Center in the hospital every week.

Cathy and Brandon were busy on our first visit to the Cancer Center, so Bella and I were on our own. We walked down a long, carpeted hallway, the sun streaming in floor-to-ceiling windows. It was the dead of winter and the sun felt wonderful. We moved through the glass doors into the Cancer Center and the woman behind the desk tried to hide her surprise.

I introduced myself and told her that Bella was a therapy dog and that we’d wanted to visit the infusion room. I couldn’t hide my pride as I said “therapy dog.” It had been five years with so many ups and downs, so many times when I wasn’t sure she’d pass her tests, but we had finally made it.

“May I pet her?” she asked, coming out from behind the desk.

“She’s a little shy,” I explained, as Bella backed up. “Head-shy.”

“Oh, she doesn’t like me,” said the woman.

“No, that’s not it. She’s new to this work and it’s going to take time, that’s all. We plan to come every week so she’ll get used to you.” Then I added, as though this explained everything, “She’s a rescue.” I hoped that the image of a dog abandoned or abused would give Bella permission to be afraid, although I knew so little of what happened to her in Puerto Rico that I realized this was hardly an excuse.

The receptionist offered to show us around, starting with a waiting room made up of comfortable chairs, potted plants, and bright art work. I couldn’t tell if the people sitting there were patients or families waiting for patients. Off to the side was a gurney where a young man lay. He was covered by a white blanket and was fast asleep. I stared at his face—he was so young and yet looked ravaged—all bones and sunken flesh.

Joy Unleashed

Joy Unleashed